By Erin Kelly, originally published in the November 2023 issue of RE Magazine, the flagship publication for NRECA.

In sub-Saharan Africa, scenes from the early days of the electric cooperative movement in America are being replayed.

Like U.S. farmers in the 1930s and ’40s, people in Liberia, Uganda and Zambia are partnering with NRECA International to prove once again that the co-op model can bring light to remote rural communities that are largely ignored by private investors.

And they are beginning to overcome skepticism from some government officials and lending institutions about whether rural residents with limited education and experience can govern their own power companies.

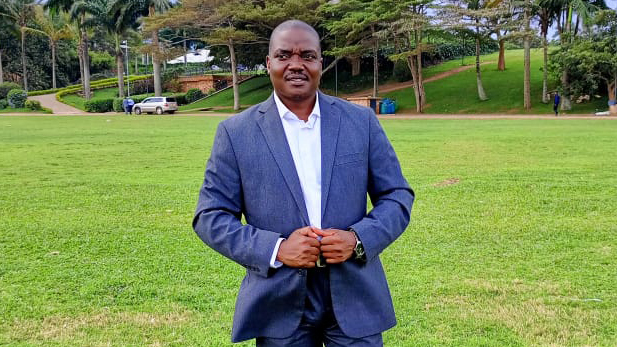

“The first day we went to see the [government] regulators, some laughed at us,” recalls Charles Matovu, general manager of the Kyegegwa Rural Electricity Cooperative Society, located about 120 miles west of Kampala in Uganda. “They said, ‘I can’t believe they think they can do this.’ Even the community members could not believe that we the people could manage this business.”

Co-ops have a long history of overcoming doubters, says Dan Waddle, senior vice president of NRECA International.

“In the U.S., the first option was not to create electric co-ops,” he says. “The government offered loans to investor-owned utilities in urban areas to go out and serve rural communities, but very few of them took those loans. The co-op model was their second choice.”

It took a great deal of public education, Matovu says, to convince his community that electric co-ops could work as successfully as they have in the U.S. and other nations throughout the world, including the Philippines, Bangladesh and Latin America.

Today, KRECS, which began operating a decade ago, serves about 9,000 people connected to the national grid. Last year, NRECA International co-financed a solar-powered minigrid with CoBank to provide power to 120 homes in a small farming village about 20 miles from Kyegegwa.

Power from the co-op has allowed people to start their own small businesses, use computers inside their homes, keep food and drinks refrigerated, visit internet cafes, do schoolwork at night and undergo treatments at local medical centers, Matovu says.

New schools, religious centers and government offices have opened as a result of economic development spurred by access to electricity, and there is growing demand to expand the co-op’s service.

“There’s been a big change in the lifestyle of people,” Matovu says. “People do believe in co-ops and appreciate them now.”

Finding financing

Still, finding financing remains the biggest challenge in creating co-ops in sub-Saharan Africa, Waddle says.

“There is a lot of financing available for government-owned utilities and privately owned utilities seeking financing from equity markets or partners,” he says. “A growing amount is available for small, private startups that are very high risk. If you look for financing for cooperatives, there is nothing available.”

For-profit investors are naturally drawn to areas with the biggest populations and highest education levels, Waddle says.

“But what about the rest of those communities?

Who’s going to serve them?” he asks. “It’s the very same scenario that led to the creation of the cooperative program in the U.S. Co-ops often exist because of a market failure. When individuals see they can’t get access to capital on their own, they join together to form their own companies.”

Innovative approaches

At Totota Electric Cooperative in Liberia, initial public skepticism about co-ops has turned to voracious demand from neighboring communities for the life-changing power enjoyed by TEC’s 2,500 members.

“We have communities around Totota that, if they’re not connected soon, I see an uprising,” says Aaron Massaquoi, the co-op’s general manager. “They ask, ‘Why do other communities have it and we don’t?’”

TEC, created with contributions from U.S. co-ops, has become a role model for the region, becoming financially self-sufficient less than two years after it began operating in 2018.

NRECA International offered the kind of training, advice and technical expertise that the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utilities Service once gave to fledgling U.S. co-ops. It also provided the crucial solar-powered minigrid that brings power to the co-op’s members, who don’t have access to the national grid.

Totota has become an economic hub for local entrepreneurs who are now able to sell cold beverages and refrigerated food to travelers making the long trek from the capital city of Monrovia to Ivory Coast.

Despite its success and the strong demand for electricity, TEC still struggles to get affordable financing to expand service to neighboring communities, Massaquoi says. The co-op has come up with innovative approaches, including a “donor conference” last summer to try to raise money from business leaders in Liberia and the U.S.

“The loan situation in Liberia is a little bit difficult,” Massaquoi says, with interest rates ranging from 15% to 25%. “This has made us choose not to go for a loan and to try other things instead.”

Shifting the mindset

Emily Varga, a cooperative business specialist with the U.S. Agency for International Development—which helps fund many of NRECA International’s projects—says rural communities are frequently underestimated and the cooperative model misunderstood.

These communities “often need an additional ‘push’ in the form of external resources, infrastructure and technical assistance,” she says. “That is where USAID programming and the support of NRECA International can come in.

“Additionally, model cooperatives—such as Totota—can help shift the local mindset to see these entities as modern businesses that are versatile and agile and meet the economic and social needs of their communities.”

The creation of co-ops in Liberia and Uganda has helped pave the way for a community in northern Zambia to begin the process of forming a co-op of its own.

In July, more than 150 people gathered in Ntatumbila for the inaugural general assembly of the Ntatumbila Power Electric Cooperative Society. They approved co-op bylaws and elected a board of directors. If all goes as planned, electricity from a solar-powered minigrid should start to flow to about 400 homes by the end of 2024.

The Zambia Electric Cooperative Development Program is funded by USAID and implemented by NRECA International in partnership with the Zambia Rural Electrification Authority.

About 600 miles southwest of Ntatumbila, in the community of Petauke, NRECA International is also working with the REA to conduct energy assessments and educate residents about the benefits of electric co-ops in preparation for potentially creating a co-op there.

Communities that have the most potential to succeed have key characteristics such as economic activity, community cohesion and access to land to support an on-site power supply—like a minigrid—in areas that are too remote to connect to a national grid, Waddle says. They also should have trusted leaders and be able to operate a co-op that is big enough to support an adequate revenue stream, he says.

Varga sees plenty of reason for hope in the region.

“I’m particularly optimistic about the tenacity of youth to discover and optimize the cooperative model in creative and innovative ways,” Varga says. “I’ve also been humbled by the ongoing commitment from the U.S. cooperative sector in promoting and supporting cooperative development abroad. These relationships are founded on a common belief in the power of the cooperative model to do amazing things.”